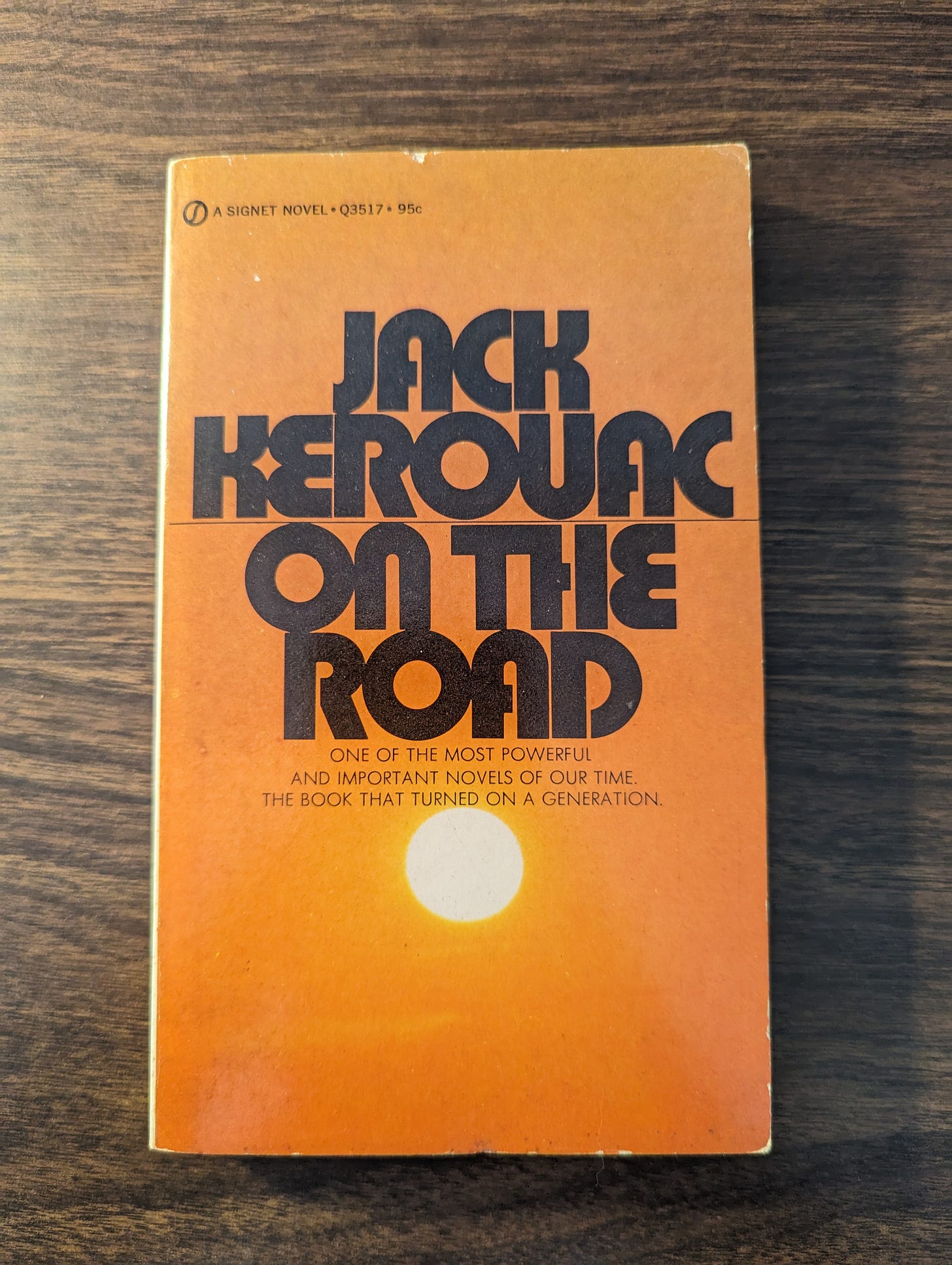

I first read Kerouac when I was about 19 years old. I was late to the party, but I’ve always been the last one in the pool. I found out about him the way most do, through “On the Road.” I read that Bob Dylan once said the book changed his life, and when you’re 19 and working the night shift, you’re always looking for something to change your life.

To set the scene; I’m 19, it’s my second year of college, and I’m attending a small liberal arts college in the Pacific Northwest. I’m on the search, I’m looking for the answer that I thought college would give me, but all I’m met with is the reality that the scholarship I was awarded to attend college, to move out of the auto parts warehouse my parents and I had moved into when I turned 18 and we went broke, had run dry after the first year, not to be renewed no matter how many applications I sent in. The next thing I knew I was down in the dishpit of the university– cleaning dishes for a conjoined Subway and Panda Express, my arms perpetually covered in chemical burns from the industrial cleaners, my shoes sopping wet. The cruelest thing about this– though not cruel like war or famine, but a duller type– was that I was not alone. All around campus men and women with faces and stories like mine were in their own dish pits; behind service counters, cleaning bathrooms, taking out trash, or quietly consumed stacking paper cups in plastic holders. I was not unique at all, but one of many students who had been lured to attend a university with scholarships and carrots and sticks, only to have their scholarships cut off after their first year, and then finding themselves stuck, suddenly in some amount of debt, suddenly far away from home, working the moments they weren’t in class in silence to help pay for the mess they’d found themselves in. And in this way it wasn’t wrong at all, but according to a plan. The mobility of college becomes a sort of illusion the kids from foreclosed homes and outskirt apartments buy into, the night shift workers, the closers alike, they’re all caught in the same dream, not realizing the slight of hand done on them until they’re cleaning some dirty bathroom mirror for long enough, catching their eyes in it’s reflection, and realizing they’re right back to where they were before, serving a different client.

In all this I’m given a copy of “On the Road.” I’m consumed by the book from morning to night, reading between classes and on my breaks in the library, rereading and underlining to keep it going as long as I can. I’m reading between lines and feeling like I’m having a private conversation with Jack– like most crazy people do with books they find early on in their life. In my eyes, working these jobs, holding them all close to my chest, I feel a kinship to the late, reluctant leader of the Beat Generation. And I too have friends from all over the place– tug boat sailors, grocery store clerks, security guards and more– and suddenly the book seems like an answer, that the way out isn’t some great epiphany, or sacred knowledge found in school, but to live day to day with a sort of romantic vision of your own life.

The slight of hand Jack pulls is part wonderful and part exploitative, but not without its share of sympathy. Jack travels with pack in hand and spends nights on floors, in the woods, and in the back of cars, plenty of which I’ve done myself (and done well enough to know the romance of things like this fades quickly if you’re not drunk). The exploitation comes when you realize the people he becomes infatuated with and writes so beautifully about are a means to an end, and seldom treated as whole people. The sympathy he writes of, loving each person, thing, or place, comes only once he’s cast each character out of his life for the next one, feels bad about it, and goes on the hunt for the next “it” (a phrase he repeatedly uses to describe living in the moment, that beautiful trancelike state where you feel like you understand the meaning of it all– also one partially dependent on booze).

What comes to mind when reminiscing about all this is the fantastic ending of the book at hand, when the now somewhat-recognized Kerouac (or his alter ego Sal Paradise) gets an attaboy for his book “The Town and the Country” hops in a limo with the New York literati, and passes his dear old friend Neal Cassidy on the street corner, who he’s just traveled back and forth around the country multiple times with. Kerouac’s new high society friend asks him if he knows the Colorado kid high on the corner, a big “moth-eaten overcoat” on his back, looking like a vision of hell to the comfortable folks in the car. Keroauc shrugs it off, knowing Cassidy’s presence would ruin the affair and cast a shadow on his otherwise new life as the hot new writer. They leave Cassidy alone in the night, but not without Kerouac feeling a twinge of discomfort for his decision. But despite this feeling of woe, to Jack, their time is now over, their story has ended.

Like anyone who read the book, after that first read I thought it was a sort of gospel. And much like Jackass or any dangerous TV show, this book should contain its own version of the “Don’t try this at home” warning. But this isn’t apparent after the first read. In the first read all you get is the language, the scenery, and unlike many books, a leading man who is working class but appreciates poetry, who finds art to be masculine, and is ultimately torn by a seemingly beautiful world in disarray, seeking to make it right by following a path of debauchery and constant movement. To see this book and all it preaches as an “answer” to anything is similar to solving a multiple choice question by filling in the bubble that’s closest to the answer, but knowing you used the wrong equation. But how can you tell a 19 year old anything?

Taking the work as gospel, I organized a road trip of my own to Southern California with a group of friends from high school, myself the only one in college pursuing a sort of “Spring Break,” the rest of my pack simply putting in for time off from their respective jobs, excited that something was happening. After a year of being apart by time constraints, work, college and the rest, we were back together like the good old days.

I didn’t book campsites, motels or plan a single thing. I figured we would wing it. The destination was vague, the great monolith “Salvation Mountain” in the desert just outside of Slab City, Niland, CA. I found a picture of it in a book and set it as the “X” on our long trip down the coast. Salvation Mountain was built in the 80’s by artist Leonard Knight, the original one destroyed by a torrential downpour– which Knight considered a message from God to build a bigger, safer monument. Around 1989 Knight had figured out the formula and continued the building process for decades afterwards. He had built a mountain with his hands, stating it was a message of “unconditional love to humankind.” It seemed romantic enough.

Three of us started the journey south (myself, and my friend’s Colin and Nick from highschool), and on our first day down to Oregon picked up our good friend Ben who had recently docked a tugboat and was living in a trailer, growing dope, in Astoria, OR. It was all the rage that Ben was back around, not seeing much of him since after highschool. Ben was always the guy who had the best pot, and had a running list of ways to get high using just products from the Dollar Tree. He was, and still is, one of my closest friends, while also being that sort of small town mythic figure I can’t help but bring up anytime I’m back around my hometown. He had been paying his way through community college by selling pot to college kids and working nights off and on at a Pizza Hut.

Once we had picked up Ben we started making real time. He took the wheel, and as he always did, gunned the car at 100 miles per hour. He was a great driver, but always seemed distracted with everything except the road before him– at one point nearly careening us off a highway trying to read the label of his energy drink, and another time taking a lengthy call with a friend telling them where to buy LSD that night, all the while snaking us through a winding mountain path, one hand on the steering wheel, his gas-foot planted firmly on ground, running my old Honda Civic flat out as we sped past signs with warnings to slow down.

That first night out we found a campsite by some lick of luck just off the Oregon Coast. We picked up a rack of beer using an old ID my brother in law had given me (although we looked nothing alike), and drank, playing a drunken game of leapfrog through the freezing ocean until around midnight. At some point Ben pulled out a flashlight he had gotten while working on the tug, claiming it was “explosion proof.'' None of us really knew what this meant. But pointing it towards the highway just above the water Ben yelled, “Watch this!” He clicked it on and the beam lit up bright as the sun, turning the whole black night a bright yellow, and causing cars on the highway above to swerve. We all laughed about this, finished the beer, and cooked cans of beans over the campfire before having a short, wet sleep in our rain soaked tent.

Ben had told us all about the boat, and Colin, Nick and I hung off every word. He had sailed up and down the coast pulling barges of paper goods, and had pictures of sunrises over the water. It all seemed far off to us, who were respectively working the long night shifts at our pizza shops, grocery stores, and restaurants. I’m not sure how the conversation got to this point, but one of us asked if people ever died on the boat, to which Ben responded a woman had been cut in half by a crossing of lines, like hot wire through a ripe melon. He explained how they would bag 'em up and store them until land. We all nodded.

Making time was a big part of the trip. We all had about a week off, and the road down to California, if you take it slow and take in the scenery, is about 3 days. But after Oregon we were so excited to get to the beach and the desert, Ben and I took long shifts driving the whole vertical length of the country in about 16 hours, playing conversational catch-up nonstop for hours the whole way down. He was interested in college and I in the boat, and like back in highschool we swapped stories, played music the other had never heard, laughed and screamed while Colin smoked and Nick passed out on a handful of edibles in the back seat. It was decided years ago that Nick wasn’t allowed to drive after an event that took place in Eastern Washington, where Colin, him and I took a camping trip and Nick, behind the wheel after filling up at a Chevron, peeled into oncoming traffic nearly getting us t-boned. Nick didn’t drive after that. And being old friends from years back, set in our tribal ways, never allowed him to try it again. It was the way of things.

In the dead of night, delirious and in need of sleep, Colin took the wheel and got us to Los Angeles, and everything seemed to be right and real the second we saw those huge city lights.

Colin had an epiphany as we debated where we would sleep, and where we would go next, to call Jake, a friend from highschool that had moved to San Diego to attend college. We gave him a call, and he was thrilled at the idea of seeing the Boys, telling us if we could get down to San Diego he’d have a place for us to stay, not realizing we had been sleep deprived and rain soaked for the last 24 hours. Nick whipped up Whiskey Sours in the back seat (we called him the Car-tender) and we raced the additional 3 hours south to San Diego.

The four of us had been “The Boys” since highschool, and everyone knew it. We were bonded early on, and although I don’t remember the first time we all got together, we had a standing date every Friday to go and spend the night out at Ben’s grandparents house, who he house-sat for about half the year while the old snowbirds flocked to the Southwest to get some warm air, leaving the dead, Northwest winter, and their house, behind. For 3 years of highschool, every Friday, all four of us would go to the big house near Summit Lake, each of us bringing a bag of weed, and smoke the night away.

We had routines and rituals we would do on these nights. We always had to wait in the school parking lot for hours until Ben got off work at the Classy Chassis. Nick, Colin and I would habitually go hang out at the Goodwill nearby, smoking in the parking lot, trying on funny clothes and kicking rocks until we got the call from Ben that we could come over. The night routine went something like this; we would all show up at the big house, turning off our headlights the last quarter mile so none of the neighbors would be the wiser– there was always the great impending fear of being “busted.” We would unload our bags in the house and each take our respective rooms– Colin in the grandma’s room, Nick sleeping in the basement, Ben on the main couch, and myself in the grandpa’s room. This was never deviated. Then would come the time where we all showed off whatever weed we had managed to score, which always seemed like a feat, but looking back on it today, they were mostly small bags of mid-tier stems and branches. We’d either smoke outside by the trash cans or hotbox the garage bathroom, laughing and laughing until we were faint. Then we’d throw on the TV and either Colin or I would break into the grandpa’s office to take out this letter opener shaped like a sword and swing it around, as was the routine.

We’d play elaborate games of hide and seek in the big 2 story house– one particular time, especially stoned, we couldn’t find Nick anywhere, and after hours had gone by, with him not answering to our screams or even picking up his phone, we found him curled up on the deck, shivering in the December wind on a piece of outdoor furniture, muttering out, “This rooms so cold.” But perhaps the most important ritual was the long drive we’d take into town to get food at the Safeway. We always loved a drive. We’d pile into Ben’s Volvo, banging on the sunroof, shaking cans like maracas to “make a beat,” where we’d scream songs by Alabama or Kansas over the racket until we made it into town. There are other stories from our nights at that house– the time Nick tried to cut off Ben’s arm with a pizza cutter, the vodka we watered down, and the night we all sat on the roof of Ben’s Lexus while he drove around the woods, where Ben, driving, climbed up too for a second before the car started to swerve out of control– but those are mostly insider-bits that wouldn’t mean much to anyone besides the four of us who were there for them.

Years later when explaining all this to a friend, she asked “Did you ever have girls over? Why didn’t you throw a big party?” And until that moment the thought had never crossed my mind. And though on 2 occasions we did bring over an outsider, we would always agree that they had somehow ruined the atmosphere. They’d make fun of the rituals, the songs, or ask why we didn’t just buy food first and not drive into town stoned out of our minds at midnight. These things we couldn’t answer. Habit doesn’t make sense sometimes, and we’d always end up reverting back to our core rituals, just the four boys. It was all we needed.

By the time we got to San Diego it was 3 or 4 in the morning and Jake was asleep. He wouldn’t pick up his phone. And with only an address to a huge college apartment complex– no apartment number, no door code, no nothing– we were screwed for the night. We drove around slowly considering our next move. After debating if we had enough money for a motel for the night we ended up finding a public park that looked good enough to sleep in. But just as we were about to unload at the park and spend a night huddled under a jungle gym, Jake picked up, and we were saved. Jake's place made all our apartments, trailers and spare bedrooms look like peasants quarters. A big couch, 4 big rooms and the usual college-ephemera covered the walls of the cushy apartment. It was a real vision of American college– far different than my little squat up in lonely Bellingham, Washington, and we all took it in. We took hot showers, cleaned up, and after shooting the shit with Jake over some Rolling Rocks, staring out at the ocean from his top floor view, passed out until noon the next day.

We ate breakfast with Jake at a Mexican restaurant and walked the beach for a while. All four of us wanted photos of us by the ocean, as if to prove we really did something, and if nothing else, or the car broke, or we were to actually spend a night under a jungle gym, we had at least done that much. We turned out of San Diego quickly, waving off to Jake, heading back north towards Joshua Tree, where we hoped to stay for the night before Salvation Mountain. Passing the windmills and red rocks until we ended up in Joshua Tree, we were all enamored by the great desert expanse, the great “raw rolling land” Kerouac had written about, my paperback book still in my backpack, still far from the tragic ending of the novel, but this was no time for books.

After scouring our phones for a place to sleep we stumbled upon a mom and pop campsite, who let us sleep in the back for a twenty dollar bill. We headed to a local Walmart for some more onions and beans and beer for dinner, and while walking through the aisles I had received a phone call I had been waiting months for. In the dreary Washington winter, halfway through my second year of college I had applied for a grant to study abroad in London for the summer, and my application had been approved, and the funding squared away. I was going to be on a plane to Heathrow in a couple months. I told this to all the boys and it was the talk of the town– no one could believe I was about to go to Europe, especially me. It seemed so regal and impossible, but it had happened. Ben congratulated me with a chunk of shoplifted pepperoni in his mouth that he was hacking off a log with his trusty “pepperoni knife.” Everything was wonderful and hazy right then, and with two racks of beers under our arms we made our way to a closed Home Depot to steal firewood for the night from their enormous dumpster. And after a dinner of beans, Ben and I picked up huge flaming 2 by 4’s and fought with them like swords out in the desert until we fell asleep. As Ben and I curled up in a big Mexican blanket on a deflating air mattress, I could hardly fall asleep with all the excitement of everything about to come. I was as far away from my dishwasher job as I could be.

The next morning there was a sandstorm and we could barely put the tent away. The car had overheated and we spent a few hours sitting on the red dirt before pussyfooting the old Honda into town for some gas station coffee. We decided then and there, at least Ben and I, that this day was just right to drop some acid and wander around the desert. Ben had brought, as he usually did on any trip, about 20 hits of acid, and a bag full of yellowish molly. It was good to be prepared. We scrapped the last bit of our money together to rent a Motel 8 for the night in 29 Palms– base camp. Just as we had loaded our gear into the room, Ben and I ate up a tab of paper each and I threw Colin the keys to take us into Joshua Tree’s national park. Once out there the drug began to take hold and the Honda felt like a boat rocking on some distant, thrashing waves. Colin swerved us around, laughing as Ben and I adjusted our Arco sunglasses on our face and held onto the door handles. Nick and Colin didn’t want to trip, they were more interested in watching us– the couple of time’s Nick tripped he had a rough time, and wasn’t looking to chance it again. Our first time tripping Nick turned to me and said “I hear the wolves, Ryan,” and ever since then approached it with a heavy caution.

Once we got off the beaten path enough, parking in a huge square of dirt, we decided we would go climb a mountain. We saw one in the distance, with its huge orange peaks and deemed it suitable to scramble up. As we walked towards the summit Ben screamed “Jack rabbit!” and ran off towards some hallucinatory specter, the rest of us chasing after him until we all became a bit lost. After that we made our way to a huge rock structure we had seen in the distance. I’m not sure to this day if it were the drug, or just the overwhelming sense of glee, but Ben and I scrambled up the near sheer cliffside like Billy Goats, finding a foothold there, and a way to pull ourselves up here, with Nick and Colin puffing behind us all the way. Ben and I had to refer to Colins judgment a few times on jumps we thought we could make, calling for our “Sober Eye.” And thank god we had him, because most of the leaps we would’ve attempted would’ve been death sentences, but everything seemed possible with that twitchy, reeling high out there in the hot sand.

I lost track of time, but eventually we made it to the top of the mountain, and the entire landscape looked like some huge map, everything flat and infinite, spreading out far before our eyes, only cut off by the horizon line. It was at this moment that we all realized how high up we were, and looking down at the cliff face we had just scaled, discovered other climbers far below us, making their own cautious ways up– all of them with helmets, harnesses and ropes.

We took our time coming down. There was a healthy bit of fear in all of us, but Ben and I laughed like maniacs the whole way down– jumping from rock to rock yelling out whatever crazy thought came into our heads. At the base of the mountain Colin asked if we wanted to take a picture, and just then, as Colin snapped the shot of Ben and I with arm around each other's shoulders under the prehistoric red rocks, we noticed an enormous gash on Ben's right leg, dripping blackish purple blood into his shoe. I screamed and Colin told Ben to look at his leg, which he laughed off.

We headed back to town to doctor Ben up at the Walmart. Colin and Nick went off to find bandages and instructed Ben and I to stay right where we were. We tried, but after a few minutes there was just too much to see, and we wandered away. People stared as we made our way around, bumping into this and that, taking time to feel the material of shirts and laugh at racks of pots and pans like they were the strangest things we’d ever seen. Everything was alien. Somewhere along those infinite linoleum floors Ben turned to me, lowering his shades, and in a paranoid shout I could only imagine he intended to be a whisper, yelled, “Do you think everyone’s staring at us cuz’ we’re on ACID?” Right then the quiet and polite shoppers looked at us with equal parts disgust and concern. I turned to Ben and shouted back, “They’re staring at us cuz you’re bleeding everywhere!” And turning around Ben noticed the healthy trail of blood on the floor, oozing steadily from his leg like bread crumbs to find our way back home.

We made it back to the Motel and Colin bandaged Ben’s leg up. All Ben could do was laugh and ask for a smoke. After that we killed some time by putting hot dogs on all the fire sprinklers, shouting, and wrestling around the stained carpet floors. Eventually we ended up in the Motel’s hot tub and stayed there for what must have been about 5 hours, but what felt to me at the time to be years.

Once we had planted ourselves in the jacuzzi, we took in our view; the great tar road out of 29 Palms that led back through the dunes to Los Angeles and straight on to the Pacific ocean. The more I looked at it the more I was convinced that the single road headed the opposite direction, back East, probably stretched all the way to the Hudson river, to the Atlantic, and then off to England. When I tried to narrow my eyes to see where the end may be, the snaking road began to move, becoming longer and I gave up trying to understand. Everything was bright green from the jacuzzis lights, and with the few palm trees above us, and the warm neon glow from a Pizza Hut sign right across the street, I began to feel deeply at peace, sinking into the warm water like a cinder block.

Lots of time passed there but it was hard to tell from the drugs. We stayed far longer than the recommended 30 minutes the sign above us mandated. We watched people come and go, other travelers. A young couple fought with each other, sprawled out in lounge chairs, the man threatening to throw her in the pool, then the woman firing back that if he did, adjusting her wig, then he’d be sleeping outside. A German tourist, silent, in a tight fitting speedo sat by us for a while, his eyes darting sharply around as Ben and I talked about taking ayahuasca the next day, and smoking marijuana in the run off ditch behind the motel. We asked him if he knew what this was and he smiled and nodded dumbly. I was convinced for a while he was with the police, but I couldn’t prove it. Finally, as the night burnt on and the motel manager stared at us through the lobby’s plastic blinds, watching the clock, waiting to eject us at 10, there came these boys with crew cuts.

They were two young army boys, each with a big, cheap cigar in his mouth, and they just sort of laughed. From time to time they looked at each other, and looked at the cigars, and the palm trees, and smiling these almost scandalous smiles, getting away just for a moment from the base– probably thinking they were really “somewhere” right then. And when they sat down in our jacuzzi, arms to their sides, spitting up the remnants of those one dollar cigars, it seemed as if they had come there just for us– guests for some kind of imaginary, drug fueled, hot tub talk-show.

Ben and I talked non stop with questions about what they did, who they were, where they came from and why they were there. Colin gave us a sober-eyed look, we were scaring them with our interrogation, and after dipping my sunglasses, finally seeing the two wavy blobs I was transfixed on become human, with eyes and lips and confused, scared grins, I realized that we were. But they were nice. Army boys. Training. 18 and 19. Base right down the highway. On a night's leave. Looking for “girls'' they said– but with an air of naivety and a scent of cheap cologne, as if they hoped they’d find prostitutes around the single strip of cheap motels but didn’t know who to ask, or where to look, or even what that exactly was besides a vision they had from the movies.

At one point they asked where we were from, and I said Washington. One of the boys said that it’s cold up there. The other nodded. I said that everywheres colder or hotter depending on where you come from, and they smiled politely and laughed frightenedly. Ben and I had been on the come down, when the twitch began to eaze up but the manic energy lingered. At one point the two army boys tried to have a conversation alone, but Ben caught word that they were talking about a mine field– they were mine sweepers.

“It’s like anything.” One of the boys said, puffing his cigar, making a face like he wanted to throw it out. “You just try not to blow yourself up.”

They both laughed. And then Ben laughed. But I just stared at them through the dark lenses of my sunglasses in the night.

“What if you step on a mine? Does anybody ever step on one?” I asked.

“Oh yeah.” They both nodded nonchalantly.

“Well isn’t that frightening? That you could die doing that?”

The two boys looked at each other and shrugged. And I can’t remember which one said it, maybe both said it, but it rolled off their tongue simple as a mother calls a child's name, as if they’d been conditioned to say it by some recruiter, or some sergeant, or some government official, or some father out there somewhere;

“Everybody’s good for one.”

I don’t remember leaving the hot tub, or if we got the Army boys names, but I remember sitting in a runoff ditch with Ben, coaxing a pipe of pot to light and talking about everything we could think of under the stars. I told him I was going to write a book and we’d all be in it, and everything that's happening now was so important, and how this is so real– realer than the dishpit. He understood and agreed. We wandered around outside for a while and threw eggs at buildings until we got tired, then went to sleep.

We ended up making it to Salvation Mountain and saw it, and as soon as we could snap a few photos, we knew it was time to go, to burn out and get back to Washington before all our shifts started up again and life continued. We drove through the night, and after a brief day trip to what we thought was a bathhouse of natural hot springs, and turned out to be a Bat-House– a bat sanctuary in the middle of the Oregon woods– we raced back to our respective places in the world– back to the Pizza Huts, grocery stores and dishpits. It was a bittersweet ending from a long vision of car windshields, cheap campsites and the passing countryside, but we all gave those solemn nods long-lived friends give when they leave eachother again, not sure the next time they’ll all be back around.

The next thing I knew, while everyone else worked through the long summer, I was getting ready to take a series of connection flights to Heathrow to study abroad. In some ways I was a fraud of the very thing that tied us together– working class kids looking for kicks. And though my financial situation was the same, I was flying away from it all to study English literature in another country, to meet people of the world, to find the next thing without taking everyone else with me. At this point I had written out everything that had happened on the trip, and would read it over again and again, stare at the photos we had taken and try to tap into it again, but you can’t ever really go back to something like that– that defining trip that bonded you to your friends, the recklessness that can only come to the young, and the feeling of being against it all, whether it be weather or injury or hallucination. I was leaving everyone behind. I had finished the end of “On the Road” and couldn’t help but see my departure to England and experiences no one else was having as my own sort of limo pulling away from the people I knew. And though my time abroad was not nearly as devastating as Kerouac’s image of quite literally going into another kind of life, I could see how my actions to try and find “more” signaled a changing of the tides between me and everyone else leant up against their truck back home.

The four of us had other road trips, we kept it alive. And although some of our subsequent trips still stand in my mind as the greatest times of my young life, it was never really the same after I came back from England. We were always just chasing that first time down the coast. The trips that ensued after, with the Boys and without, were more dangerous. I took stints of sleeping outside, I lived in a van, I tried different drugs, I broke down on highways far away from home, I had run-ins with the police, periods of homelessness and all manner of troubles trying to chase down that first trip, to get that feeling I had when it was just me and the boys and my book. It took its toll in a way chasing a memory should never do.

On our last roadtrip all together, we tried to drive my van to New Orleans and we broke down in Logan, Utah just a day or so after we set out. We were all drinking heavily, we were using more drugs, and it all seemed a part of the process– our rituals. We limped the van to a Chevy Dealership, and after a night of sleeping in the parking lot Nick told us he was going to rent a car and drive back home. He claimed things were getting out of hand, there were too many drugs for him, it was unorganized, and all the things that defined our past trips, with the passing of time, seemed immature to him– dangerous even. Nick handed me a hundred dollar bill and said good luck. He drove off, and after ten years of friendship and travel, we never saw him again.

It all seemed like fun and games at the time, but today I question my motives for it all, and why I kept this memory so close to my chest that it destroyed part of the greatest friendship I’d ever had. But I guess everybody’s good for one.

Years later while studying at Columbia, I was working on writing a book following a slew of minimum wage jobs I held. Throughout the chapters I would submit to my professor– those stories of burning beer cans in the woods, sleeping in my van, scrubbing floors for bitter bosses with little understanding– he made a remark about how the biggest obstacle the project faced was for me to admit I was a class-traitor. I remember at the time thinking he didn’t get it. He didn’t realize I was still the dishwasher living against the world. But after our meeting, myself sat in an apartment in the upper west side, warm bed, not a single work uniform in my closet, teaching creative writing classes, I saw how far away I really was from it all. I started to glean how maybe holding on to this memory of myself as the kid at the dishwasher was some way of holding back the floodgates of what I was now– not wanting to be the fraud, the sellout, or the guy leaving his friends behind once he wanted more. If memory could just hold on long enough, maybe I would never have to change who I thought I was, maybe I could hold back on reading the final chapter once more, make it last a little longer, if not for nostalgia but for some sort of self preservation. I spent the night getting drunk on my stoop and feeling sorry for myself.

I would re-read Kerouac as if looking for answers, as if to come back to question the very advice I was given. But just like that first time down the coast I realized the book could never live up to the first read, when I was young and broke and needed it. And in each re-reading of the book I found more and more of the worst parts of myself present– the need to use certain people to have certain times, a dependence on substances to find excitement, the nature of wanting to document not for the genuine sake of preservation but to have something to say “Look at me!” and to support the notion that as I got further from my roots, moving to bigger cities, going to an Ivy League school, of saying “I still go it! I’m still that boy with the pack on his back, on the road.”

When I look at the book today I think of myself. I see a lot of naivety in it. I see a certain time. But mostly I see how Kerouac straddles the line between the genuine and the class traitor, and gives it up to all the kiddies to see far before they know they have anything to betray.

Kerouac died in 1969, vomiting blood and later passing away at a Florida hospital. It was his damaged liver that prevented the surgery that could have saved his life. He was 47. I didn’t know the exact particulars of his death until years after reading all his work. I was initially disturbed that it wasn’t a Hemmingway shotgun or a drunken stupor that got him, but a quick death preceded by years of abuse, a far and tragic cry from anything he could’ve written.

Like most young men reading Kerouac, more than wanting to be like him, I wanted him to be like me. He was beautiful, but deep underneath all that was a confused man, a man eventually done in by his own image which was worshiped by people just like me, imitating any stunt he would do in a debauched devotion. Although I liked to think at the time that I would’ve had a lot to talk about with him, it became clearer to me after reading his biographies that behind the writing was just a man who enjoyed sitting alone in a chair with his bottle, a man whose life on the road was a brief period in an otherwise sullen life of silent boozing and a less than noble obsession with the “Beverly Hillbillies.” Kerouac once said in a French interview, “I am not a brave man,” and maybe that’s the hard truth in it all. I got so consumed in the idea that he was Sal Paradise that I forgot he was writing a story, and unlike stories, life doesn’t have clean endings, martyrs or absolute characters.

Very good stuff sir